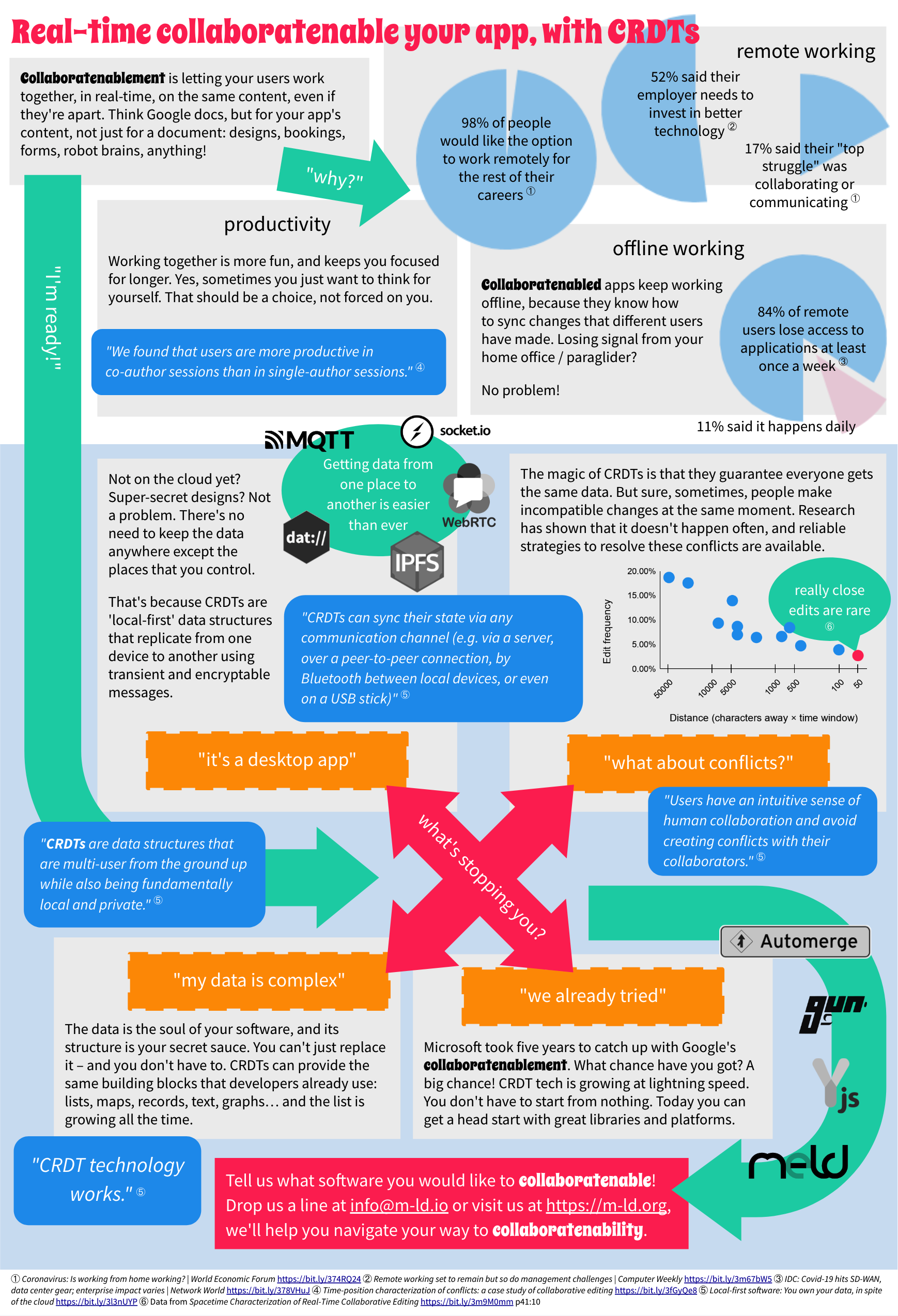

In The Data Æther I envisioned a future abstraction for data, X, in which its syntax is invisible, its semantics are always visible, and we always know how close to the truth it is. So we no longer have to wrangle data between software components, and we can get on with adding value and solving real problems.

Let me tell you about where this vision has led me, personally. I’m a practical type, and I’m only comfortable selling hopes and dreams if I can show that important parts of the dream work in a real life.

So I’ve been building m‑ld, which is like X in microcosm. It doesn’t try to change everything about software architectures, all at once. Instead it’s a practical step in the right direction, which delivers some new value.

That new value is all about live information sharing among collaborating actors, such as app users, software layers, or autonomous robots. m‑ld reduces the cost and complexity of coding information sharing, allowing the faster delivery of apps, information services and control systems. Think real-time editing features, like Google docs, but for any structured information.

So as well as making some choices that suggest a direction for X, m‑ld is deliberately targeted at one corner of the truth axis, the hardest one to get right, which is having some information be writable for multiple actors at the same time. It’s not the first or the only library for that, but by anticipating X it has a strong commitment to a data representation with inherent extensibility to new data structures and rules, and also new truth claims. It also tries to be as ergonomic as possible, and come with everything you need to get going.

Just recently I’ve put these claims to the test, by extending m‑ld with a new data structure. As of today, m‑ld natively supports Lists.

Sarcasm, from a monkey. Photo by Jared Rice on Unsplash

I know… Lists!

Yes indeed, the data structure that’s used by every program that ever goes beyond “Hello, World”. But bear with me. Here are some other technologies that don’t have Lists as a native construct:

The latter is particularly relevant here, as we’ll see in a moment. But relational databases, and good old SQL? The foundation stone on which some 60% of data applications are built, doesn’t have Lists?

Yes — and deliberately so. In designing the relational model, one of Edgar F. Codd’s goals was data independence, the ability to describe data without dependence on how it is serialised in storage.

… in recently developed information systems… the model of data with which users interact is still cluttered with representational properties, particularly in regard to the representation of collections of data

He singled out ordering dependence, because of its tendency to be driven by serialisations implicitly ordered by sequential addresses (like arrays) or pointers (like linked lists).

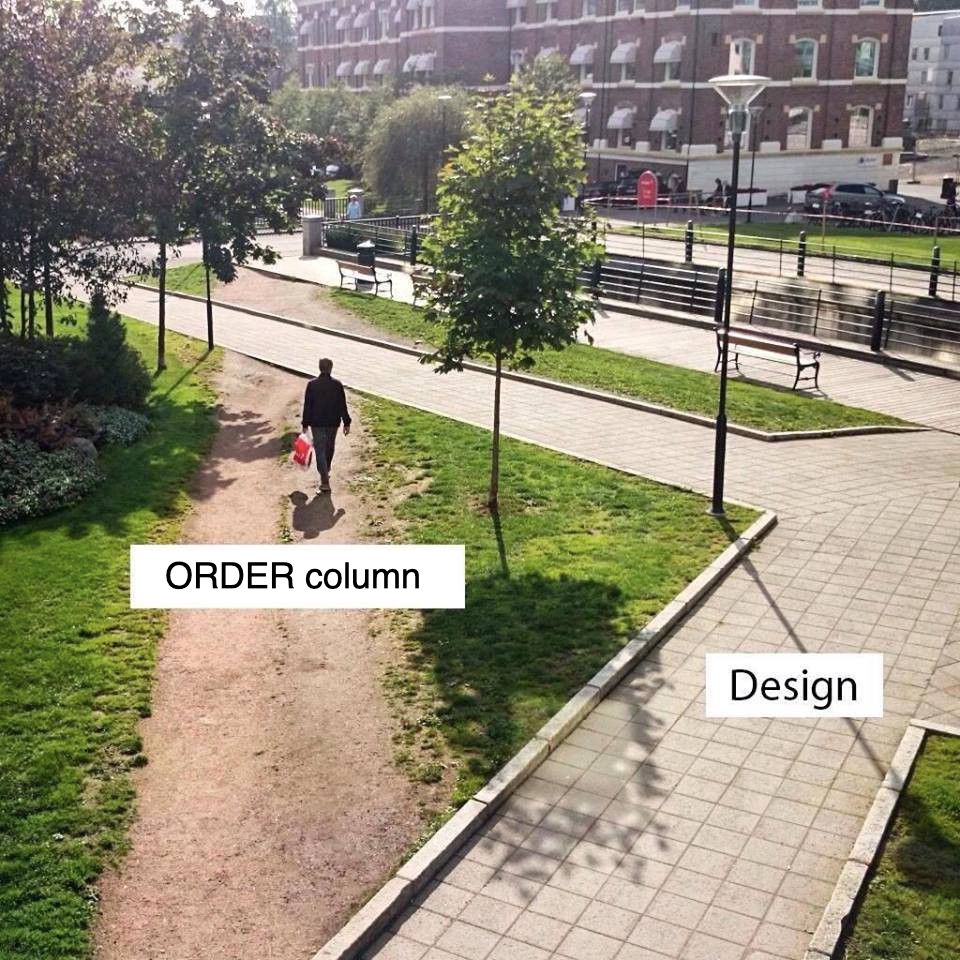

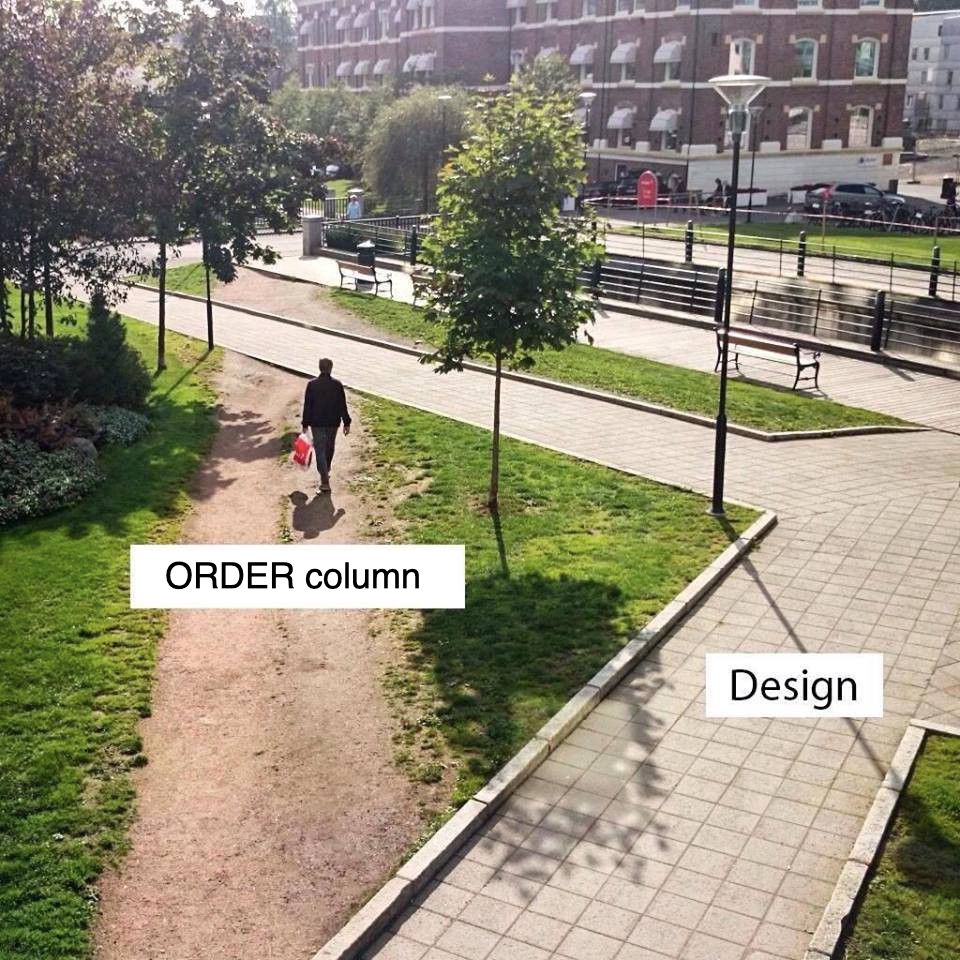

His solution was to insist that order of presentation is not implicit, but driven by some order-able component of the data itself. So in his model, Relations (e.g. tables) are strictly unordered Sets of rows and columns. Fast-forward to the twenty-first century and we find the database world littered with ORDER columns containing integer list indexes.

‘Experience’ versus design, applied to Lists in a relational model (original source unknown)

So Codd’s concept of data independence, applied to Lists, essentially means that the ordering of the list must be explicit in the data. But if so, an application needs a way to enforce the correctness that ordering, for example:

-

Lists are either empty, or have a first element and a last element

-

The position of any list item unambiguous

-

Lists do not have gaps, cycles, or branches

These kind of rules fall into the domain of data consistency, which Codd initially accounted for with constraints and was augmented by the work of Andreas Reuter and others in consideration of the ACID properties of database transactions.

Consistency. A transaction reaching its normal end (EOT, end of transaction), thereby committing its results, preserves the consistency of the database. In other words, each successful transaction by definition commits only legal results…

As Pat Helland points out, this property allows for “a more cohesive semantic enforced by an application”. In other words, an application and the database collaborate on what constitutes a “consistent” state.

So, despite sowing confusion, this model has undoubtedly found considerable success. Why does m‑ld need Lists then?

JSON-LD and Why…

m‑ld’s foundational data model is not the Relational Model but the Resource Description Framework. RDF has even stronger data independence and an even simpler data structure: in RDF, a whole database is just a Set of triples: each a statement with three parts, subject, predicate and object.

This confers a number of advantages, but the main one is that data structures, all the way from sets to tables, to lists, to a robot’s worldview, can be layered on top in a consistent, seamless and well-defined way. This is critical for m‑ld, which offers a different model of concurrency control, broadly categorised as eventual consistency, which affects behaviour in all these structures and layers. We’ll go into this a lot more.

But at the same time, we didn’t want to have to invent a new data representation to achieve this. RDF is well-defined, has a formal query language (SPARQL), a number of serialisations, and library mappings to various programming languages.

That’s the positive side. However, while RDF has its fans, I’ll let Manu Sporny, the inventor of JSON-LD, exemplify its detractors and provide a convenient segue:

RDF is a shitty data model. It doesn’t have native support for lists. LISTS for fuck’s sake! The key data structure that’s used by almost every programmer on this planet and RDF starts out by giving developers a big fat middle finger in that area... For all the “RDF data model is elegant” arguments we’ve seen over the past decade, there are just as many reasons to kick it to the curb. This is exactly what we did when we created JSON-LD, and that really pissed off a number of people that had been working on RDF for over a decade.

For all the vitriol, I’ll hazard the suggestion that JSON-LD is an important boon to RDF. It’s worth reading the linked article for the motivation, but with JSON-LD, Manu et al. created a serialisation syntax for RDF that bridges a gap from academia to the real, dirty practices of software developers out in the world, solving problems.

So given that opinion, you will not be surprised to learn that m‑ld’s interface supports JSON-LD as its (currently, only) data serialisation syntax.

What Dreams May Come

So, we started this endeavour with a conundrum: RDF doesn’t natively have Lists, any more than the Relational Model does, and there is a good reason, in data independence, for this to be so. But Lists are so ubiquitous, and so valued, it’s hard to even imagine a new data management component that lacks them as a first-class citizen.

The escape hatch that we chose, is to treat API and implementation separately:

-

m‑ld’s API has native Lists, just like JSON-LD does.

-

m‑ld implements Lists as an extension to its core data model.

By implementing Lists we have ‘eaten our own dog food’ and exercised the same inherent extensibility that we offer to apps that use m‑ld. Lists have no free pass to do anything that an app data structure cannot, except for having some syntactic sugar in the API.

And boy, did we eat a lot of dog food.

“Whatever will I do with you.” Photo by Brooke Cagle on Unsplash

There were two hard problems that we faced.

-

JSON-LD has Lists, but it doesn’t have a way to update them.

We had already extended JSON-LD with our query language, json-rql, which includes an update syntax derived from SPARQL. To accommodate list updates at specific indexes, though, we had to slightly break the JSON-LD @list syntax, while staying true to its spirit.

-

RDF Containers and Collections can’t cope with concurrent editing.

“Wait, you said RDF doesn’t have Lists!” Not in its core; but it does define some terms which capture some of the semantics of collections. Unfortunately, the terms define structures that are very brittle in the face of concurrent edits, and so, unusable in m‑ld.

Let’s dive in.

List Updates

By default in JSON-LD, array values are unordered sets. This is startling, considering that here is a technology deliberately created to look and feel like JSON — and the first thing we mention about it, is a departure from one of JSON’s core semantics (and there aren’t many of those to depart from).

But this is actually a great example of JSON-LD’s core pragmatism. JSON-LD is a graph data model, and a serialisation format for RDF, in which set semantics is more fundamental than array semantics. So the designers were between a rock and a hard place: either they break JSON a bit, or they break with JSON, invent their own syntax, and throw away the default support of thousands of tools and libraries.

To mitigate this, with an out-of-band annotation you can turn array semantics back on for fields that are definitely lists and not sets, or you can do the same in-band by way of a keyword, @list, which interposes between the property and the array, like this:

{

"@id": "reminders",

"phone": ["Alice", "Bob"],

"shopping": { "@list": ["Bread", "Milk"] }

}

In this example I’m reminded to phone both Alice and Bob, without any prejudice as to which one first or their relative priority. For the shopping, the @list keyword tells me that the order of Bread and Milk matters (rather mysteriously — why it matters is not specified).

The ordering of a List in JSON-LD will survive the various canonical transformations that a JSON-LD processor supports, including translation to RDF (of which more in a moment). But that’s it, really. There’s no syntax for adding new items or deleting existing ones; updates are not part of JSON-LD.

Enter json-rql, a superset of JSON-LD, designed for just that. The above JSON-LD example is already json-rql, describing an initial insert of graph data into some store. But now I can update my phone reminders with an update ‘pattern’:

{

"@delete": {

"@id": "reminders", "phone": "Bob"

},

"@insert": {

"@id": "reminders", "phone": "Claire"

}

}

This means I don’t have to phone Bob any more, but now I do need to phone Claire. The shopping is unaffected, because @delete and @insert represent patches to the existing data. Note also that "Bob" and "Claire" don’t need to be in square brackets because in the graph data model, a value is equivalent to a singleton set.

Why the boldface? Because that, right there, is a subtlety that can really bite. What does this mean:

{

"@id": "reminders",

"shopping": [

{ "@list": ["Bread", "Milk"] },

{ "@list": ["Pink Wafers", "Spam"] }

]

}

Yes, you guessed it, it’s a Set of two shopping Lists. You can try it on the JSON-LD playground, it’s completely valid.

But, if I were to try and @insert Angel Delight into the shopping, which list would it change..?

So here’s one way that json-rql parts ways from JSON-LD, just a little, within its ‘superset’ remit. In json-rql, Lists are promoted to full-blown Subject nodes, and can therefore have an @id:

{

"@id": "reminders",

"shopping": [

{ "@id": "buy", "@list": ["Bread", "Milk"] },

{ "@id": "avoid", "@list": ["Pink Wafers", "Spam"] }

]

}

If you don’t provide an @id m‑ld will generate one for you, which will be visible when you do a query.

We can now uniquely identify the list we want to update, and so without further ado, here is the syntax for removing Bread from the “buy” list and adding Cheese at the beginning:

{

"@delete": {

"@id": "buy", "@list": { "?i": "Bread" }

},

"@insert": {

"@id": "buy", "@list": { "0": "Cheese" }

}

}

In the interests of brevity I just hit you with a few things at once; let’s unpack them.

-

List updates can use an indexed-object syntax instead of an array for the @list key. (If you’re familiar with Javascript this may not be surprising.) An index key must either be a variable, or parseable as a non-negative integer.

-

For the @insert, we specify the (zero-based) index we want Cheese to appear. A JSON key cannot be a number, so we wrap it up in quotes. (In Javascript, you can use a plain number.)

-

For the @delete, we don’t care which position Bread is in, so the index is a variable i (we could equally use an anonymous variable). If Bread appeared more than once in the list, this would delete all occurrences.

This indexed-object syntax also allows us to perform pattern matching against the list by index or item, or both. If I want to know which list Spam is in, and with what priority:

{

"@select": ["?list", "?spamPriority"],

"@where": {

"@id": "reminders",

"shopping": {

"@id": "?list",

"@list": { "?spamPriority": "Spam" }

}

}

}

This returns [{ "?list": { "@id": "avoid" }, "?spamPriority": 1 }].

You can try out this Lists API in m-ld using the web-based playground. Here is a link to the example. (Once the domain is connected, just click apply in the Transact pane to insert the list.)

So now we can express list operations in the json-rql API. How does this translate to the RDF graph?

RDF List Representation

A JSON-LD processor, when asked to produce RDF, will convert a @list field into an RDF Collection, which is a pattern for encoding the list items into the graph without losing the ordering. Here is our shopping list in N-Triples format:

<http://ex.org/reminders>

<http://ex.org/#shopping> _:b0 .

_:b0

<http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#first>

"Bread" .

_:b0

<http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#rest>

_:b1 .

_:b1

<http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#first>

"Milk" .

_:b1

<http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#rest>

<http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#nil> .

Let’s trim this down with a simplified notation:

reminders shopping o .

o first "Bread"; rest p .

p first "Milk"; rest nil .

Where o and p are internal identifiers (note that the _:b0 and _:b1 above do not capture list index numbers, just the order in which the identifiers were generated).

Even if you’re not familiar with RDF and the syntax, hopefully you can see that the general pattern is a linked list. If you’re interested in the details, Ontola has written a nice article about this and other RDF options.

I’ll mention, in passing, that even though it can be done, this arrangement is a megalithic PITA to query with SPARQL, RDF’s query language.

But as a linked list, this structure also requires care when editing, to keep the list valid. In a programming language you’d encapsulate the delete and insert operations into functions, and preferably hide away the pointers so consumers of your list don’t accidentally make a mess of it. In an app, you can do the same for consumers of the RDF data.

A bigger problem is what happens when this structure is edited by multiple actors concurrently, which is a core requirement for m‑ld.

As we’ve noted, m‑ld uses a Conflict-free Replicated Data Type (CRDT) to ensure that every clone ends up with the same data. But using the plain RDF Collections pattern, concurrent edits generate ‘lists’ with an amusing cornucopia of empty positions, loops, gaps, and branches, even if all the edits were valid by themselves. Distributed systems veterans will not be surprised by this. But how to get around it?

Constraints

There are a number of existing languages for declaring the structure and rules of RDF datasets, including SHACL, RDFS and OWL, which provide a powerful toolset for information and knowledge engineering. It is very much the intention that users of m‑ld will have the option to use such tools.

However, these do not generally consider the particular demands of concurrent editing. So, for now we’ve been inspired by them but taken our own path with a lightweight way of declaring constraints (similar in spirit to Codd’s, hence the name).

A ‘constraint’ is a semantic rule that describes not only invariants about the data, but also encapsulates update rewriting, conflict resolution and entailments, as we’ll see. If that makes them sound like a bit of a sonic screwdriver, that’s pretty accurate.

“Scanner, diagnostics, tin opener!” Everything an adventurer needs for the incredible journey ahead!

In fact ‘constraints’ are an API that permit apps to define their own semantic rules in code. It’s still very much an advanced function, because of the need for the implementer to consider concurrency, unlike the normal app API.

Is it possible to use constraints to fix the the concurrent behaviour of RDF Collections? The simple answer is: we didn’t even try. (Although, if you feel like giving it a go, let us know.)

Enter LSEQ

The reason we very quickly elected to drop RDF Collections as a representation for Lists, is that it requires post-hoc resolutions to conflicting updates. This is supported by constraints; but the cost is that each resolution appears in the history as another transaction (the original transactions that generated the conflict already being committed). RDF Collections are so dramatically prone to conflicts that the marginal comfort of using an existing pattern just doesn’t balance the costs.

And of course we’re committed to data independence, so we can readily use a different representation if that gives us better mileage.

So, is there a way of representing Lists that doesn’t generate conflicts? As mentioned, there are a number of sequence CRDTs (recall that the C stands for Conflict-free) that have been characterised. Can they be overlaid on the RDF data model?

Yes. Here is our shopping list, once again:

<http://ex.org/reminders>

<http://ex.org/#shopping>

<http://ex.org/buy> .

<http://ex.org/buy>

<http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type>

<http://m-ld.org/RdfLseq> .

<http://ex.org/buy>

<http://m-ld.org/RdfLseq/?=pmkHiW2fz54xWz98Q>

"Bread" .

<http://ex.org/buy>

<http://m-ld.org/RdfLseq/?=qmkHiW2fz54xWz98Q>

"Milk" .

And in abbreviated format (note, m‑ld’s network and storage representations are closer to the below than the above):

reminders shopping buy .

buy type RdfLseq ;

RdfLseq/?=pmkHiW2fz54xWz98Q "Bread" ;

RdfLseq/?=qmkHiW2fz54xWz98Q "Milk" .

The URI http://m-ld.org/RdfLseq is a class name and namespace for a List CRDT based on LSEQ. We mark the list as belonging to this class to allow for future list CRDTs doing something different.

The characteristic of LSEQ visible here is that it uses an order-able position identifier for each item in the list. Yes, it’s an ORDER column! But the way the position identifiers are generated guarantees that:

-

Position identifiers are unique to a clone;

-

Position identifiers do not change; and

-

It’s always possible to position a new item in between two existing ones.

This means that clones can generate new position identifiers independently of each other, and maintain a global ordering in which the user intentions are always respected, without coordination or conflict.

(There’s an additional indirection involved in the actual representation to handle moving items in the list and maintaining numeric item indexes, via list slots. We’ll go into that another time. For a preview, have a look at Martin Kleppmann’s paper on moving elements in list CRDTs.)

Key to the way we implemented this, is that there is no RdfLseq-specific code in the core of m‑ld. It’s all done in a constraint:

-

Rewriting json-rql @list updates to RdfLseq position updates

-

Entailment of numeric item indexes for querying

-

Resolution of the one kind of conflict that can still rarely occur: duplication of a list slot

At the moment the prototype DefaultList constraint is available and active in the Javascript clone engine, and the constraint features are documented there. Of course, they will also have a section in the full m‑ld protocol specification as it beds down, and we work towards our Beta release.

Conclusion

In this article we discussed the theoretical basis for Lists not to be included among the primitives of a representation that seeks data independence; but their importance in practice deserves recognition.

So in m‑ld, Lists are an interface primitive but not an implementation primitive, which has led to the expansion and clarification of the extension API for data constraints.

In order to achieve an efficient convergent list data type in RDF, the foundational data representation used in m‑ld, we chose to bypass the RDF Collection terms almost entirely, and to slightly modify the JSON-LD List representation. We hope to engage more with the communities around these technologies to inform future developments.

If you’re interested in live information sharing with m‑ld, do get in touch! We’d love to hear about your projects.